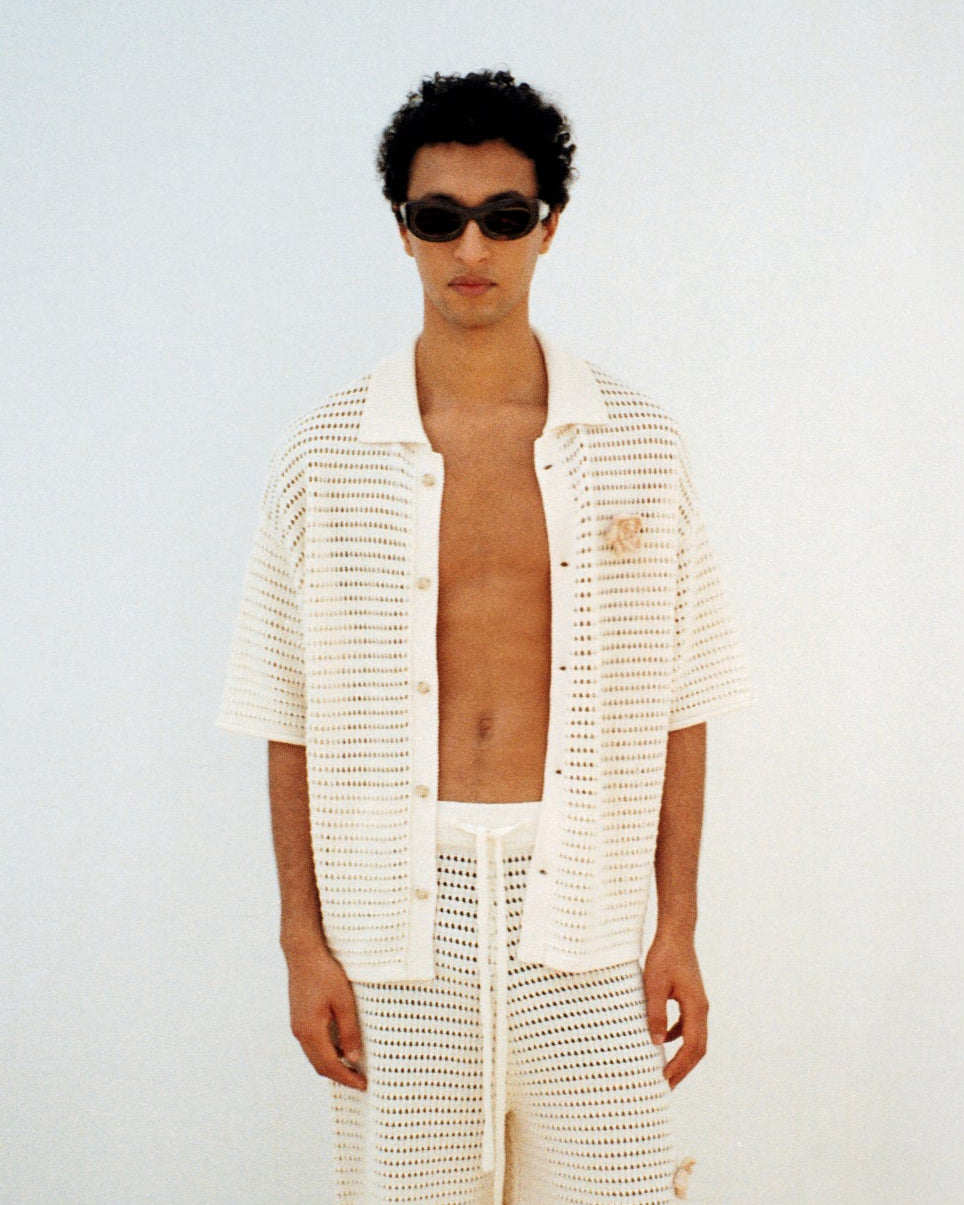

In Conversation With

ADRIAN PEPE

Honduran-born textile virtuoso Adrian Pepe weaves together disparate threads of cultural narrative with exquisite technical precision. Our paths intersected during the COMMAS x OUNASS Dubai launch, offering a moment of meaningful exchange.

Anchored in the rich tapestry of Levantine craftsmanship, Pepe's practice represents a soulful collaboration with artisans whose hands carry generational knowledge. His work - at once reverential and revolutionary - transforms ancient weaving techniques into contemporary expressions of identity and memory. Through this material dialogue, Pepe not only preserves disappearing traditions but elegantly subverts the conventional boundaries between craft and high art, creating tactile poetry that speaks to both past and present.

How would you describe your profession to someone who knew nothing about you?

My practice uses fibre, especially wool, as a way to think through systems of labor, ecology, and ritual.

It often begins with a raw medium and ends somewhere between object and gesture, where the process itself becomes the work.

What first drew you to fibre arts, and how has your relationship with textiles evolved over time?

I came to fibre through architecture, initially drawn to structure, tension, and material systems. But textiles offered a different kind of engagement: something more immediate, more intimate, more tactile.

You work with fibres that carry history within them. How do you decide which materials to use?

I don’t always “choose” materials in a deliberate way. Often, I come across them through proximity, through encounter, something clicks, sometimes it doesn’t.

I’m drawn to what they can hold, but more importantly, to what they resist. Sometimes a material speaks to a larger system I’m trying to understand. Curiosity plays a role, but so does friction.

Textiles have long been woven into the fabric of history, telling stories of people, places, and movements. Is there a particular historical or cultural narrative that has profoundly influenced your work?

I often return to the figure of the sheep as a cultural agent. Across Abrahamic religions, the sheep has been central to sacrifice, exchange, and pastoral ethics, shaping human notions of care, ritual, and power.

The sheep reappears in contemporary mythology, Dolly, the first cloned mammal, born from a ewe.

From ancient offering to biotechnological prototype, the sheep has continuously been a site of projection: of belief, utility, and experimentation.

Working with wool is entering into/within that continuum, asking how these relationships have been constructed, instrumentalised, or forgotten.

What began as material interest became a deeper inquiry into gesture and embodied knowledge. I started thinking less about what textiles do, and more about what they carry, ecologically, historically, and politically.

"From ancient offering to biotechnological prototype, the sheep has continuously been a site of projection: of belief, utility, and experimentation."

You collaborate closely with artisans to preserve and reinterpret ancient weaving techniques. What have these collaborations taught you about storytelling?

I don’t approach collaboration in a traditional sense. While I do sometimes work alongside artisans, it’s not with the goal of preservation or revival. I’m more interested in the knowledge embedded in gestures - how touch and labor become a form of memory, and function as tools of inquiry.

Techniques like felting or spinning aren’t simply functional. They’re performative, rhythmic, and rooted in the body.

They carry something forward, loosely, durationally, across time.

As someone who works with time-honoured techniques, how do you see the role of tradition in a rapidly changing, digital world?

I’m cautious of how we use the word “tradition.” It often implies something static, inherited intact. But in reality, tradition is mutable; it shifts through repetition, through interruption, through use.

I’m drawn to these techniques not to revere them, but because they involve the body as an instrument of thinking. They’re tactile, recursive, and they trace the beginnings of mechanisation. These gestures sit at the root of both craft and industry.

So, tradition, if it exists here, is less about preservation and more about reenactment. It’s a form of remembering through doing. And while it's often positioned in contrast to the digital, I see an overlap. The word “digital” itself comes from the Latin digitus, the finger.

The hand is present in both realms, typing, coding, spinning, touching, and still within manual dexterity. And in that sense, still entirely contemporary.

“I'm drawn to these techniques not to revere them, but because they involve the body as an instrument of thinking."

Your art feels deeply personal yet universally resonant. Beyond the studio, how do your daily experiences, travels, or even quiet moments shape your creative vision?

I move between periods of saturation and withdrawal, exposure and absorption. Travel plays a role, but not in obvious ways. Sometimes it's about proximity to material, other times about encounters.

Daily life tends to shape things. Observation matters. Stillness, too. I try not to separate the studio life from the rest.

The work doesn’t begin or end in one place, it unfolds over time.

Looking ahead, what stories or concepts are you eager to explore in your future projects?

I’m drawn to ideas around belonging and origin—not as stable identities, but as shifting conditions.

Lately I’ve been thinking about the friction between systems, and in what emerges from those collisions—the tension between inherited forms and those adopted, between what is remembered and what is made anew.